Mohamed Farrah Aidid

Mohamed Farrah Aidid | |

|---|---|

محمد فرح عيديد | |

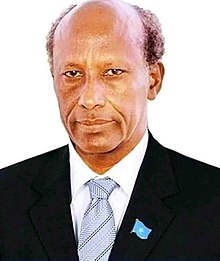

Aidid in 1995 | |

| President of Somalia | |

Disputed with Ali Mahdi Muhammad | |

| In office 15 June 1995 – 1 August 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Ali Mahdi Muhammad |

| Succeeded by | Ali Mahdi Muhammad |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 December 1934 Beledweyne, Italian Somaliland[1] |

| Died | 2 August 1996 (aged 61) Mogadishu, Somalia |

| Political party | United Somali Congress/Somali National Alliance (USC/SNA) |

| Spouse | Khadiga Gurhan |

| Alma mater | Frunze Military Academy |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1954–1960) (1960–1969) (1969–1984) (1989–1992) (1992–1996) |

| Years of service | 1954–1996 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Battles/wars | |

Mohamed Farrah Hasan Garad (Somali: Maxamed Faarax Xasan Garaad, 'Caydiid Garaad' ; Arabic: محمد فرح حسن عيديد; 15 December 1934 – 1 August 1996), popularly known as General Aidid or Aideed, was a Somali military officer and warlord.

Educated in both Rome and Moscow, he first served as a chief in the Italian colonial police force and later as a brigadier general in the Somali National Army. He would eventually become chairman of the United Somali Congress (USC), and soon after the Somali National Alliance (SNA). Along with other armed opposition groups, he succeeded in toppling President Siad Barre's 22 year old regime following the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in 1991.[2] Aidid possessed aspirations for presidency of the new Somali government, and would begin to seek alliances and unions with other politico-military organizations in order to form a national government.[3]

Following the 5 June 1993 attack on the Pakistanis, the SNA—and by extension, Aidid—were blamed for the death of 25 UNOSOM II troops, causing him to become one of the first wanted men of the United Nations. After the US-led 12 July 1993 Bloody Monday raid, which resulted in the death of many eminent members of his Habr Gidr clan, Aidid began deliberately targeting American troops for the first time. President Bill Clinton responded by implementing Operation Gothic Serpent, and deploying Delta Force and Task Force Ranger to capture him. The high American casualty rate of the ensuing Battle of Mogadishu on 3–4 October 1993, led UNOSOM to cease its four month long mission.[4] In December 1993, the U.S. Army flew Aidid to Addis Ababa to engage in peace talks.[5][6]

During a battle in Mogadishu between his militia and the forces of his former ally Osman Ali Atto, Aidid was fatally wounded by a sniper and later died on 2 August 1996.[7]

Early years

[edit]Aidid was born in 1934 in Beledweyne, Italian Somaliland.[2] He is from the Habar Gidir subclan of the greater Hawiye clan.[8] During the era of the British Military Administration he moved to Galkayo in the Mudug region to stay with a cousin, a policeman who would teach Aidid to both type and speak in Italian.[2]

Soon after, during the period of the Italian ruled UN trusteeship, a young Aidid enlisted in the Corpo di Polizia della Somalia (Police Corps of Somalia) and in 1954 he was sent to Italy to be trained at an infantry school in Rome, after which he was appointed to work under several high ranking Somali police officers. In 1958 Aidid would serve as Chief of Police in Banaadir Province, and the following year he returned to Italy to receive further education. In 1960, Somalia gained independence and Aidid joined the newly formed Somali National Army. He was promoted to lieutenant and became aide-de-camp of Maj. Gen. Daud Abdulle Hirsi, the first commander of the Somali National Army.[2][9]

Requiring more formal training, Aidid, having been recognized as a highly qualified officer, was selected to study advanced post graduate military science at the Frunze Military Academy (Военная академия им. М. В. Фрунзе) in the Soviet Union for three years, an elite institution reserved for the most qualified officers of the Warsaw Pact armies and their allies.[2][10]

October 1969 Coup d'état, Imprisonment and Ogaden War

[edit]In 1969, a few days after the assassination of Somalia's President Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, a military junta known as the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC), led by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, would take advantage of the disarray and stage a bloodless coup d'état on the democratically elected Somali government. At the time Aidid was serving as Lieutenant Colonel in the army with 26th Division in Hargeisa. He was also the Head of Operations for the Central and Northern Regions of Somalia. After the assassination, he was relieved of his duties and was recalled to Mogadishu to lead the troops guarding the burial of the deceased President. By November 1969, he had quickly fallen under suspicion by high ranking members of the Supreme Revolutionary Council, including Barre. Without trial, he was subsequently detained in Mandhera Prison along with Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed for nearly six years.[11][12][9] Aidid and Yusuf were both widely regarded to be politically ambitious officers, and potential figureheads in a future coup attempt.[13] Aidid claimed that his imprisonment was a result of encouraging President Barre to transfer power over from the Somali military to civilian technocrats.[14]

Aidid was eventually released in October 1975, and he returned to service in the Somali National Army to take part in the 1977-1978 Ogaden War against Ethiopia.[11][9] During the war, he was promoted to brigadier general and became an aide-de-camp to President Mohammed Siad Barre.[2] Headquartered in Hargeisa, Brig Gen Aidid and Maj Gen Gallel would command the 26th Division on the Dire Dawa Front.[15] After the war, having served with distinction, Aidid worked as a presidential staffer to Barre before being appointed intelligence minister.[16][17][18][19]

Under pressure from President Barre, Aidid gave a written guarantee in 1978 that Col Abdullahi Yusuf would not attempt a coup d'eat. Yusuf would go on to break the pledge in a failed coup attempt and escaped to Ethiopia. Aidid was left stranded but was rescued by a high ranking ally in the regime, and was consequently saved from any punishment.[13]

Somali Rebellion and Civil War

[edit]In 1979, Barre appointed Aidid to parliament, but in 1984, after perceiving him as a potential rival, sent him away to India by making Aidid the ambassador for Somalia.[16][17][18]

He would use his time in the country to frequently attend lectures at the University of Delhi and, with the aid of Indian lecturers at the University of Delhi, completed three books (A Vision of Somalia, The Preferred Future Development in Somalia and Somalia from the Dawn of Human Civilization to Today).[13]

United Somali Congress

[edit]By the late 1980s, Barre's regime had become increasingly unpopular. The State took an increasingly hard line, and insurgencies, encouraged by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration, sprang up across the country. Being a member of the Hawiye clan, a high ranking government official and an experienced soldier, Aidid was deemed a natural choice for helping lead the military campaign for the United Somali Congress against the regime, and he was soon persuaded to leave New Delhi and return to Somalia.[19]

Aidid defected from the embassy to India in 1989 and then left the country to join the growing opposition against the Barre regime. Following his defection, he had received an invitation from Ethiopian President Mengistu Haile-Mariam, who would go on to give Aidid permission to create and run a USC military operation from Ethiopian soil.[13] From base camps near the Somali-Ethiopian border, he began directing the final military offensive of the newly formed United Somali Congress to seize Mogadishu and topple the regime.[14]

The USC was at that time split into three factions: USC-Rome, USC-Mogadishu, later followed by USC-Ethiopia; as neither the first two former locations were a suitable launching pad to topple the Barre regime. Ali Mahdi Mohamed, an influential member of the congress who would later become Aidid's prime rival, opposed Aidid's involvement in the USC and supported the Rome faction of the Congress, who also resented Aidid. The first serious signs of fractures within the USC came in June 1990, when Mahdi and the USC-Rome faction rejected the election of Aidid to chairman of the USC, disputing the validity of the vote.[20] That same month Aidid would go on to form a military alliance with the northern Somali National Movement (SNM) and the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM). In October 1990, the SNM, SPM and USC would sign an agreement to hold no peace talks until the complete and total overthrow of the Barre regime. They further agreed to form a provisional government following Barres removal, and then to hold elections.[13]

By November 1990, the news of Gen. Aidid's USC forces overrunning President Siad Barres 21st army in the Mudug, Galgudud and Hiran regions convinced many that a war in Mogadishu was imminent, leading the civilian population of the city to begin rapidly arming itself.[13] This, combined with actions of other rebel organizations, eventually led to the full outbreak of the Somali civil war, the gradual breakup of the Somali Armed Forces, and the toppling of the Barre regime in Mogadishu on 26 January 1991. Following the power vacuum left by the fall of Barre, the situation in Somalia began to rapidly spiral out of control, and rebel factions subsequently began to fight for control of the remnants of the Somali state. Most notably, the split between the two main factions of the United Somali Congress (USC), led by Aidid and his rival Ali Mahdi, would result in serious fighting and vast swathes of Mogadishu would consequently destroyed as both factions attempted to exert control over the city.[21][22]

Both Ali Mahdi and Aidid claimed to lead national unity governments, and each vied to lead the reconstruction of the Somali state.[9]

Somali National Alliance

[edit]Aidid's wing of the USC would morph into the Somalia National Alliance (SNA) or USC/SNA. During the spring and summer of 1992, Former President Siad Barres army attempted to retake Mogadishu, but successful joint defence and counterattack by Aidid's USC wing, the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM), the Somali Southern National Movement (SSNM) and Somali Democratic Movement (SDM) (all united under the banner of the Somali Liberation Army) to push the last remnants of Barres troops out of southern Somalia into Kenya on June 16, 1992 would lead to the formation of the political union known as the Somali National Alliance.[3] This absorption of different political organizations was critical to Aidid’s approach to taking the presidency.[9]

As leader of the Somali National Alliance, Aidid, with presidential aspirations, expressed the goal of using the SNA as a base for working toward forming a national reconciliation government and claimed to also be aiming for an eventual multi-party democracy. To this end Aidid required and sought political agreements with the only two remaining major factions, the Somali National Movement (SNM) and Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), to leave his main rival Ali Mahdi Mohamed isolated in an enclave in North Mogadishu.[3][14]

Aidid's grip on power in the SNA was fragile, as his ability to impose decisions on the organization was limited. A council of elders held decision making power for most significant issues and elections were held that threatened Aidid's chairmanship.[23][24]

United Nations Intervention

[edit]In April 1992 the United Nations intervened in Somalia, creating UNOSOM I. United Nations Security Council Resolution 794 was unanimously passed on 3 December 1992, which approved a coalition led by the United States. Forming the Unified Task Force (UNITAF), the alliance was given the task of assuring security until humanitarian efforts were transferred to the UN.[25]

Aidid initially publicly opposed the deployment of United Nations forces to Somalia, but eventually relented.[2] He and UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali both despised one another. Before being Secretary-General, Boutros Ghali had been an Egyptian diplomat that had supported President Siad Barre against the USC in the late 80s and early 90s.[26] At Atto's urging, Aidid decided to welcome the deployment of American military forces under UNITAF (Operation Restore Hope) in December 1992, in part because Atto had close ties to U.S. embassy officials in Nairobi, Kenya and the American oil company Conoco.[27] In January 1993, Special Representative of the UN in Somalia, Ismat Kittani, requested that Aidid come to the Addis Abba Peace Conference set to be held in March.[28]

UNOSOM II

[edit]In early May 1993, Gen. Aidid and Col. Abdullahi Yusuf of the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) agreed to convene a peace conference for central Somalia. In light of recent conflict between the two, the initiative was seen a major step towards halting the Somali Civil War.[29][30] Gen. Aidid, having initiated the talks with Col. Yusuf, considered himself the conference chair, setting the agenda.[31] Beginning 9 May, elder delegations from their respective clans, Habr Gidr and Majerteen, met.[29] While Aidid and Yusuf aimed for a central Somalia-focused conference, they clashed with UNOSOM, which aimed to include other regions and replace Aidid's chairmanship with Abdullah Osman, a staunch critic of Aidid.[31] As the conference began, Aidid sought assistance from UNOSOM ambassador Lansana Kouyate, who proposed air transport and accommodation for delegates. However, he was recalled and replaced by April Glaspie, following which UNOSOM retracted its offer. Aidid resorted to private aircraft to transport delegates. Following the incident, Aidid publicly rebuked the United Nations on Radio Mogadishu for interference in Somali internal affairs.[32]

Aidid invited Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Somalia, Adm. Johnathan Howe to open the conference, which was refused.[31] The differences between Aidid and the UN proved to be to great, and the conference proceeded without the United Nations participation.[31] On the 2 June 1993 the conference between Gen. Aidid and Col. Abdullahi Yusuf successfully concluded. Admiral Howe would be invited to witness the peace agreement, but again declined.[33] The Galkacyo peace accord successfully ended large scale conflict in the Galgadud and Mudug regions of Somalia.[34]

Conflict with American and UN forces

[edit]The contention between the Somali National Alliance and UNOSOM from this point forward would begin to manifest in anti-UNOSOM propaganda broadcast from SNA controlled Radio Mogadishu.[31] The broadcasts were viewed as a threat to the operation and that station was searched, sparking the 5 June 1993 battle and the start of UNOSOM II military operations against the Somali National Alliance.[35] The UNOSOM offensive had significant negative political consequences for the intervention as widely alienated the Somali people, strengthened political support for Aidid, and led to growing criticism of the operation internationally. As a result numerous UNOSOM II contingents began to increasingly push for a more conciliatory and diplomatic approach with the SNA.[36] Each major armed confrontation with between UNOSOM II forces and the SNA was noted to have the inadvertent effect of increasing Aidid's stature with the Somali public.[37]

After the October 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, US President Bill Clinton defended American policy in Somalia but admitted that it had been a mistake for American forces to be drawn into the decision "to personalize the conflict" to Aidid. He went on to reappoint the former U.S. Special Envoy for Somalia Robert B. Oakley to signal the administrations return to focusing on political reconciliation.[38] The U.S. Army flew Aidid to Addis Ababa on a military aircraft in December 1993 for peace talks. He arrived at the Mogadishu airport in an American armored vehicle guarded by American forces and his own Somali National Alliance before being flown to Ethiopia.[5][6][39]

After the cessation of hostilities between the SNA and UNOSOM, Special Representative Lansana Kouyate (replacing Adm. Johnathan Howe) successfully launched an initiative to normalize relations in March 1994. Numerous points of contention between the respective organizations were discussed at length and understandings were reached, facilitating the normalization of the relationship between the UN and the SNA.[40] That same year the UNOSOM forces began withdrawing, completing the process by 1995. The withdrawal of UNOSOM forces weakened Aidids prominence within the SNA, as the war had served to unify the alliance around a common foreign enemy.[41]

Presidency declaration

[edit]Aidid subsequently declared himself President of Somalia in June 1995.[42] However, his declaration received no international recognition, as his rival Ali Mahdi Muhammad had already been elected interim president at a conference in 1991 in Djibouti and recognized as such by the international community.[43]

Death

[edit]On 24 July 1996, Aidid and his men clashed with the forces of former allies Ali Mahdi Muhammad and Osman Ali Atto. Atto was a former supporter and financier of Aidid, and of the same subclan. Atto is alleged to have masterminded the defeat of Aidid.[44] Aidid suffered a gunshot wound in the ensuing battle. He later died from a heart attack on 2 August 1996, either during or after surgery to treat his injuries.[45][46]

Family

[edit]During the lead up to the civil war, Aidid's wife Khadiga Gurhan sought asylum in Canada in 1989, taking their four children with her. Local media shortly afterwards alleged that she had returned to Somalia for a five-month stay while still receiving welfare payments. Gurhan admitted in an interview to collecting welfare and having briefly traveled to Somalia in late 1991. However, it was later brought to light that she had been granted landed immigrant status in June 1991, thereby making her a legal resident of Canada. Additionally, Aidid's rival, President Barre, had been overthrown in January of that year. This altogether ensured that Gurhan's five-month trip would not have undermined her initial 1989 claim of refugee status. An official probe by Canadian immigration officials into the allegations also concluded that she had obtained her landing papers through normal legal processes.[47]

Hussein Mohamed Farrah, son of General Aidid, emigrated to the United States when he was 17 years old. Staying 16 years in the country, he eventually became a naturalized citizen and later a United States Marine who served in Somalia. Two days after his father's death, the Somali National Alliance declared Farrah as the new president, although he too was not internationally recognized.[48]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 9780810866041.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Margaret Castagno. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1. OCLC 268778107.

- ^ a b c Drysdale 1994, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (17 November 1993). "SEARCH FOR AIDID OFFICIALLY ENDED". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b Jehl, Douglas (7 December 1993). "Clinton Defends Use of U.S. Plane To Take a Somali Leader to Talks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

President Clinton said today that he supported the decision by his envoy in Somalia to ferry Gen. Mohammed Farah Aidid to peace talks aboard a United States Army plane, but officials said they were seeking a less visible way to return General Aidid to Mogadishu.

- ^ a b Lauter, David (3 December 1993). "U.S. Flies Somali Clan Leader Aidid to Talks: Former fugitive is escorted to peace negotiations in Ethiopia by American military, which once hunted him". Los Angeles Times.

The American military, which lost 18 troops trying to capture Mohammed Farah Aidid in early October, provided the Somali clan leader with an airplane and an escort Thursday to get him to peace talks in the Ethiopian capital, leaving Administration officials scrambling to explain the latest twist in America's tangled adventure in Somalia.

- ^ Peterson 2000, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Purvis, Andrew (28 June 1993). "Wanted: Warlord No. 1". Time. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Ingiriis, Mohamed Haji (2016). The Suicidal State in Somalia : The Rise and Fall of the Siad Barre Regime (1969-1991). UPA. ISBN 978-0-7618-6719-7. OCLC 951539094.

- ^ Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part I" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ a b United Nations. Dept. of Public Information (1996). The Blue Helmets: A Review of United Nations Peace-keeping. United Nations, Dept. of Public Information. p. 287. ISBN 9211006112.

- ^ Ismail Ali Ismail (2010). Governance : the scourge and hope of Somalia. [Bloomington, IN]: Trafford Pub. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-4269-1980-0. OCLC 620115177.

- ^ a b c d e f Drysdale 1994, pp. 20–28.

- ^ a b c Richburg, Keith (8 September 1992). "AIDEED: WARLORD IN A FAMISHED LAND". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Cooper, Tom (2015). Wings over Ogaden : the Ethiopian-Somali War 1978-1979. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-38-3. OCLC 1091720875. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ a b "CNN – Somali faction leader Aidid dies". 9 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b Daniels, Christopher L. (5 April 2012). Somali Piracy and Terrorism in the Horn of Africa. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810883116. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Jonathan (1995). Losing Mogadishu : testing U.S. policy in Somalia. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. p. 29. ISBN 1-55750-788-0. OCLC 31435791. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ a b Biddle, Stephen D (26 July 2022). Nonstate warfare : the military methods of guerillas, warlords, and militias. Princeton University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-691-21666-9. OCLC 1328017938. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Drysdale 1994, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Library Information and Research Service, The Middle East: Abstracts and Index, Volume 2, (Library Information and Research Service: 1999), p. 327.

- ^ Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part Forces I" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Drysdale 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Biddle, Stephen D. (2021). Nonstate warfare : the military methods of guerillas, warlords, and militias. Council on Foreign Relations. Princeton. pp. 182–224. ISBN 978-0-691-21665-2. OCLC 1224042096.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ken Rutherford, Humanitarianism Under Fire: The US and UN Intervention in Somalia, Kumarian Press, July 2008 Archived 10 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1-56549-260-9

- ^ Bowden, Mark (2010). Black Hawk Down : A Story of Modern War. New York. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-8021-4473-7. OCLC 456177378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Drysdale 1994, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Drysdale 1994, p. 6.

- ^ a b Drysdale 1994, p. 167.

- ^ "Peacemaking at the Crossroads: Consolidation of the 1993 Mudug Peace Agreement" (PDF). Puntland Development Research Centre.

- ^ a b c d e UN Secretary-General (1 June 1994). Report of the Commission of Inquiry Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 885 (1994) to Investigate Armed Attacks on UNOSOM II Personnel Which Led to Casualties Among Them (Report). Archived from the original on 8 August 2022.

- ^ Drysdale 1994, p. 167-168.

- ^ Drysdale 1994, p. 177.

- ^ SOMALI SOLUTIONS: Creating conditions for a gender-just peace (PDF). Oxfam. 2015.

- ^ Drysdale 1994, pp. 164–195.

- ^ Wheeler, Nicholas J. (2002). "From Famine Relief to 'Humanitarian War': The US and UN Intervention in Somalia". Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191600302.

- ^ Maren, Michael (1996). "Somalia: Whose Failure?". Current History. 95 (601): 201–205. doi:10.1525/curh.1996.95.601.201. ISSN 0011-3530. JSTOR 45317578.

- ^ Oakley, Robert B.; Hirsch, John L. (1995). Somalia and Operation Restore Hope: Reflections on Peacemaking and Peacekeeping. United States Institute of Press. pp. 127–131. ISBN 978-1-878379-41-2.

- ^ "SOMALI CLAN LEADER ARRIVES IN ETHIOPIA FOR PEACE TALKS". Deseret News. Associated Press. 3 December 1993. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ^ FURTHER REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN SOMALIA SUBMITTED IN PURSUANCE OF PARAGRAPH 14 OF RESOLUTION 897 (1994) (PDF). United Nations. 24 May 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2022.

- ^ Prendergast, John (June 1995). "When the troops go home: Somalia after the intervention". Review of African Political Economy. 22 (64): 268–273. doi:10.1080/03056249508704132. ISSN 0305-6244. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "President Aidid's Somalia". September 1995. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- ^ Djibouti Conference Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Indian Ocean Newsletter, 27 April 1996 and ciiIndian Ocean Newsletter, 4 May 1996

- ^ Serrill, Michael (12 August 1996), "Dead by the Sword", Time Magazine, archived from the original on 10 December 2015, retrieved 19 March 2011

- ^ Jr, Donald G. McNeil (3 August 1996). "Somali Clan Leader Who Opposed U.S. Is Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Anderson, Scott (4 November 1993). "Tory probe into warlord's wife too late to save Lewis". Eye Weekly. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Kampeas, Ron (2 November 2002). "From Marine to warlord: The strange journey of Hussein Farrah Aidid". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

References

[edit]- Drysdale, John. Whatever Happened to Somalia?: A Tale of Tragic Blunders London: HAAN Publishing. 1994.

- Bowden, Mark. Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. Berkeley, California: Atlantic Monthly Press. March 1999.

- "Somali faction leader Aidid dies". CNN. 2 August 1996. Archived from the original on 10 March 2006.

- Lutz, David. Hannover Institute of Philosophical Research. The Ethics of American Military Policy in Africa (research paper). Front Royal, Virginia: Joint Services Conference on Professional Ethics (2000)

- McKinley, James. 'How a U.S. Marine Became a Warlord in Somalia'. New York: The New York Times, 16 August 1996.